I don’t remember the exact moment that I began to write myself another body, but it was a few weeks after my Dad died.

He died suddenly and without warning, leaving a rip in the air behind him, a ragged gap that we – my Mum, my sister, my daughter and I – are still struggling to grasp the edges of.

At first, all I wanted was to get hold of those edges and yank them back together again, like a shirt or a pair of curtains.

I wanted to suture what had been torn.

Dad’s absence felt strangely temporary. It still does.

In a lecture, which she called ‘The School of the Dead,’ Hélène Cixous says: ‘To begin (writing, living) we must have death. I like the dead, they are the doorkeepers who while closing one side “give” way to the other.’1

She goes on: ‘Writing is learning to die. It’s learning not to be afraid, in other words to live at the extremity of life, which is what the dead, death, give us.’

Cixous was only eleven years old, the same age as my daughter is now, when she lost her father, Georges, to tuberculosis. ‘The first book I wrote rose from my father’s tomb,’ she tells us.

I don’t know if I have been learning to die, this past year, but I do know that slowly, very slowly, in the almost eighteen months since Dad’s death, I have been experimenting with learning how to live.

I have been experimenting with standing in that gap that Dad left, where the edges are still ragged.

It is writing that has helped me to do this.

‘We don’t know, either universally or individually, exactly what our relationship to the dead is,’ writes Cixous, ‘but we can think this through with the help of writing, if we know how to write, if we dare write. Also with the help of dreams: they give us the marvellous gift of constantly bringing back our dead alive, with the result that at night we can talk with our dead. Each of us, individually and freely, must do the work that consists of rethinking what is your death and my death, which are inseparable. Writing originates in this relationship.’

Dad was, quite literally, there one moment, gone the next. In the aftershock of those first months, I needed to write because I needed to say all the things I hadn’t said. He could not die. Not yet.

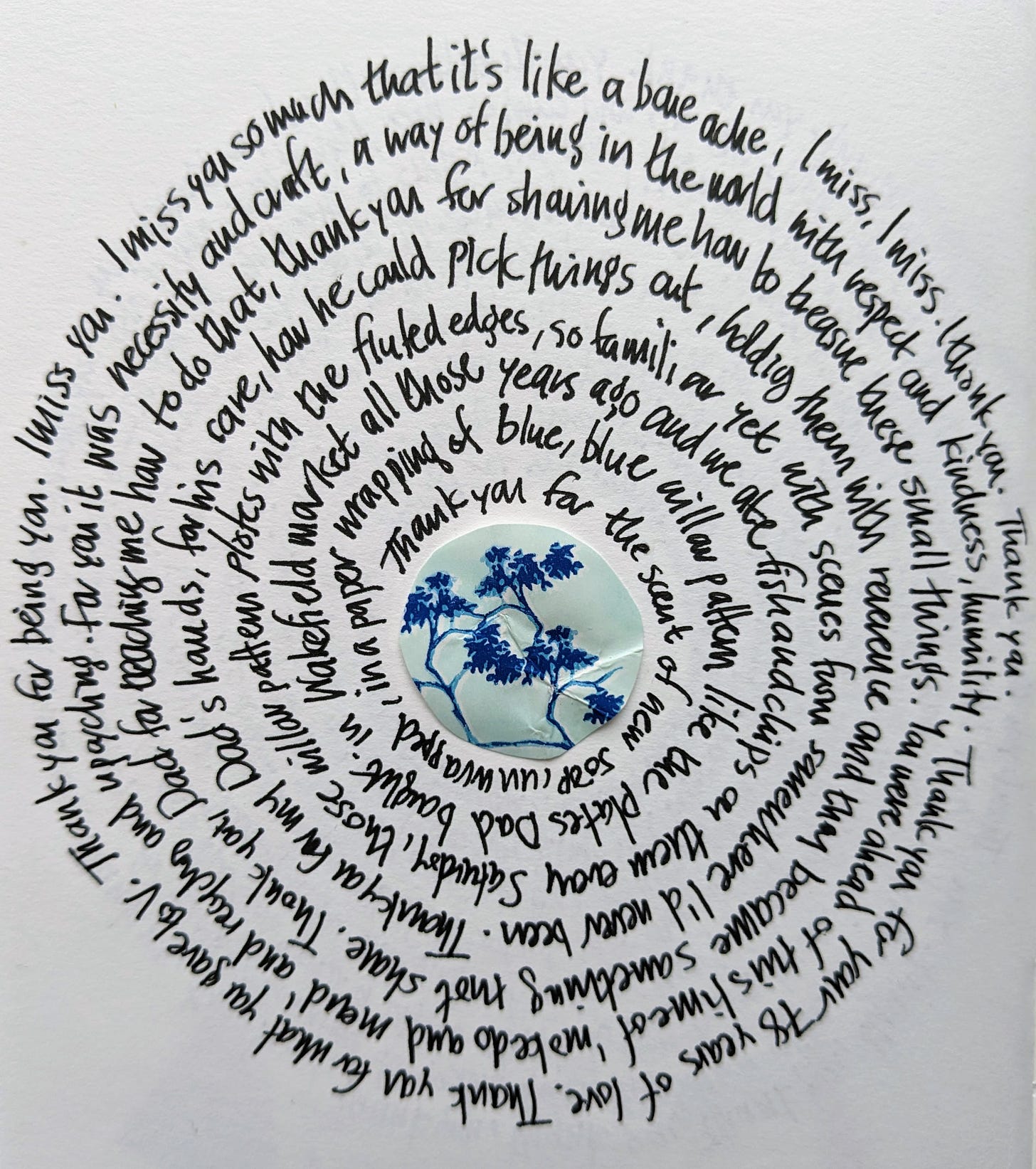

Each morning, I began with thank you. I wrote those two words – thank you – in the centre of the page and then I kept writing.

I did this for weeks and then months. It became my writing ritual. Sometimes, the words arriving on the page of my notebook were simply the sounds around me, inside the room and outside the room. I wrote thank you for the rasp of my pen on the paper, which reminded me that I was still alive, and the rhythm of my hand moving and the warmth of the sun on my face through the window.

But there were memories too. Moments that bubbled up from somewhere under my ribs, things I’d never remembered before. Bent over my notebook, I found that I could let myself cry, let myself feel in a way that I could not when I was out in the world and with other people. Writing opened the spaces inside me where I had been holding tight to my grief.

The words wound in spirals, round and round one another. The rhythm soothed me. On some days, the circles unfolded into loops and swooping lines as I wrote to Dad in love – I miss you, I miss you – and also in rage - how could you leave us like this? - and in frustration and in hope.

Sometimes I heard him reply.

The box containing his ashes sat behind me on the bookshelf in my study as I wrote. I felt his gentle presence, almost as if he were looking over my shoulder.

Cixous writes: ‘We are the ones who make of death something mortal and negative. Yes, it is mortal, it is bad, but it is also good; this depends on us. We can be the killers of the dead, that’s the worst of all because when we kill a dead person we kill ourselves. But we can also, on the contrary, be the guardian, the friend, the regenerator of the dead.’

One evening, my daughter appeared in the doorway of my study with a folded piece of paper.

‘I’ve written Grandad a letter,’ she said, laying it carefully on top of the box of his ashes. My daughter too was writing, working out her relationship with death, with the Grandad who was not yet dead to her, who remained very much alive in her own body.

‘I don’t want to forget his voice,’ she said. My daughter was – is still – guardian and friend of her beloved Grandad. She knew, immediately and instinctively, how not to kill him, how to keep him alive.

As the months went on, I realised that I wasn’t only writing to Dad. I was also writing to the small self inside me that felt afraid and alone and adrift and not good enough and full of regret and longing.

I kept writing – usually in twenty minute bursts between teaching and marking and helping my daughter with her homework – and I noticed that something was happening.

I realised that, for years before Dad died, I had not been living as fully as I might. Not really. I had been struggling, grafting, worrying. There had been bright spots of colour – but there had been a lot of keeping myself neatly and carefully apart from myself. I had been afraid to admit my sorrows to myself, my anger, my exhaustion, my frustrations and disappointments. I had been afraid to fully own my pleasures, those things I have so often longed for – such as more time to write – but which have felt so impossible to take hold of.

Writing was helping me to think this through, to step through the door to the other side.

At the age of 52, writing was helping me to learn how not to be afraid, helping me to live, as Cixous says, ‘at the extremity of life.’

Death was helping me to write a new body for myself, a body that I could inhabit more easily than my old body. In this new body, perhaps for the first time in my life, I might not need to float outside of myself, watching and observing.

This morning, from inside this body of writing, I notice the slash of light through the gap in the curtains. Inside this body, I open the back door and walk outside with my cup of coffee, even though it’s raining. I stop for a moment, feel my bare feet on the wet stones, take a big gulp of cold air.

This is the body I am living in. This is the new body I am still in the process of writing for myself.

This morning, I am not as afraid as I used to be of my wants and my desires.

I am this body.

I am alive.

Do you have an experience of writing death or fear or desire or all of these things that you’d like to share. I’d love to hear from you.

Next Writing Together live workshop session dates on Zoom:

Saturday 24 February: WRITE YOUR TRUTH! (More details soon.)

4.30pm - 6pm (UK time)

Sunday 3 March

4.30pm - 6pm (UK time)

Wednesday 10 April

6.30pm - 8pm (UK time)

When you join us for a Writing Together workshop session, you’ll find a gentle and restorative writing space where you’ll receive support and inspiration for your writing and reflection. Camera on or off, we’ll write together in response to writing rituals, suggestions and prompts and then have an opportunity to reflect on what we’ve written and the process. The first part of the workshop is recorded for everyone so that you can catch up later if you can’t join us in ‘real time’. The second reflective part of the workshop is never recorded, in order to honour confidentiality.

I send out a new Zoom link a few hours before each month’s workshop session.

Thank you, dear Writing Friends, for your hearts, comments and encouragement, all of which fuel Dear Writing and help us to build this space together. I’m so grateful to you, my members, for making all of this possible.

Let me know in the comments if there is something you’d like to see me cover in these letters. How can I support you and your writing?

Cixous, Hélène. 1993. Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing. Columbia University Press. All the quotes in this piece are taken from Cixous’s lecture ‘The School of the Dead,’ collected in this book and delivered as The Wellek Library Lectures in Critical Theory at the University of California, Irvine, in May 1990.

So beautiful, thank you. I started writing after my parents and grandmother died in 2015 (they died in a four month period) but I didn't get to the writing for another couple of years because - well other big stuff happened too - but when I started writing I couldn't stop. Writing helps me to grieve them individually rather than this mass group grief that happened closer to their deaths. One seeped into the other, I write to grieve the family we had, the family we now have - fragmented and fractured without this trio to connect us, to shore up our foundations. My grief is different eight/nine years down the line. Sometimes I'm not sure how I grieve but then I see, feel the grief come through in my writing. I wrote a post yesterday which on the surface was about writing myself to a standstill, but actually was more about finding different ways to connect with mum outside of simply writing about her in my notebook. Ooof, sorry Sophie, I'm rambling and also, the letter your daughter wrote to your dad. Beautiful.

This is so beautiful, and beautifully honest. I feel really moved, and recognise so much of this as a grieving for so much in life, and in death, and the endless re configuring that we need to do. Thank you, Sophie. Big love ❤️