Dear Writing Friends,

This is a Restorative Writing Guide where I explore a writing theme through the lens of personal wellbeing. Please do let me know in the Comments if you find this helpful and if there are topics that you'd like me to cover in future Guides. These Guides are free. They are also longer than usual. 😄 If your email cuts this letter short, you can click through and finish reading it on the Substack web site or in the app.

It’s 5.30am and I’m sitting at my desk at the top of the staircase, tucked under the eaves of the house. Beneath me, the rooms are in darkness. I am writing. Or at least, I am trying to write. I’ve been working on the same page for the last few days, working and reworking the same few paragraphs. I can’t get them right.

I stop, flick through my notebook, sit back in my chair, look up at the skylight above my head. Wisps of cloud drift, pearlescent pink, suffused with sunrise.

I watch as the pink deepens to orange. I watch as I feel my body begin to loosen, the tightness in my jaw soften, my hands relax. A tingling warmth begins in the base of my spine and, as I breathe, it moves upwards into my chest, my head.

Now my fingers are moving over the keyboard again, but this time the words come easily. I have stopped trying. I have stopped searching. Now the words are liquid, moving out of me and onto the screen through the tips of my fingers.

The next time I glance up, the sky above my head is a perfect rectangle of glassy blue. I have written five pages.

For me, writing has always been a way of paying attention, allowing my busy, spiky, overcrowded mind to slow, my body to expand. When I remember to stop trying and instead bring my full, relaxed attention to my writing, time stands still. It’s just me and my notebook or the laptop screen, tasting the words on my tongue, hearing them inside my head, feeling my breath move through my body.

I used to understand this aspect of my writing as a kind of self-hypnosis. Years ago, I wrote a book called Hypnotic Journaling. I compared writing in my journal to a trance-like state of embodied calm. These days, I would probably describe it as a mindfulness practice.

In recent years, the word mindfulness has become part of our everyday conversations. It has found its way into boardrooms and corporate policies. It has become a short-hand for wellness.

But what is mindfulness and can we say that writing is a way to practice it?

What is mindfulness?

If I were to attempt to describe what I mean by mindfulness, I would say that it is a way of being, in which we focus our awareness on the present moment whilst noticing, acknowledging and accepting our feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations without judgement.

Though popularised in the industrialised West by Jon Kabat-Zinn’s work in Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), mindfulness has deep roots in many different cultural practices throughout the world, as Amanda Hyunh writes here. It is also intertwined with practices of compassion such as psychologist Paul Gilbert’s work in compassion-focused therapy (CFT), Kristin Neff and Chris Germer’s Mindful Self-Compassion and Tara Brach’s RAIN: A Radical Practice of Self-Compassion.

But can writing be used as a mindfulness practice and, if so, how?

Bringing qualities of mindfulness and self-compassion to our writing

Perhaps many activities - any activities? - can be a means of practicing mindfulness. Some might say that this is the entire point: that mindfulness is the process of bringing a mindful quality of attention, compassion and self-compassion to our daily doing, thinking and being.

Here’s what writer

has to say about pasta making:‘If I ran the NHS I would make pasta making obligatory for the anxious; I would set the depressed up with a cardamom bun shop and ban the use of stand mixers. Hands in, hearts up.’

Just like plunging our hands into a bowl of flour and water, writing as a mindfulness practice has, for me, always been about picking up a pen or pencil and writing by hand - in my notebook or on a piece of paper.

As beloved writing teacher Natalie Goldberg (a practising Zen Buddhist) famously advised in Writing Down the Bones, it’s about ‘keeping your hand moving.’

Noticing the rhythm of my hand across the page, paying attention to my breathing and the feel of my pen on the paper helps my mind to quiet and the freewriting to flow. On some days, this is calming and centring. On other days, it is sensuous, enlivening, ecstatic. There’s a feeling of connection with something beyond my hand and the page.

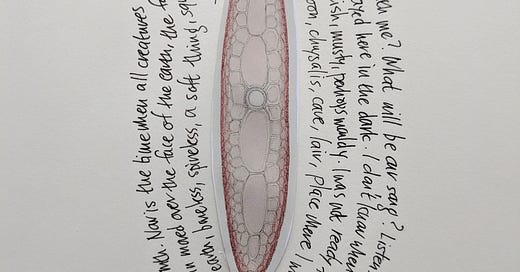

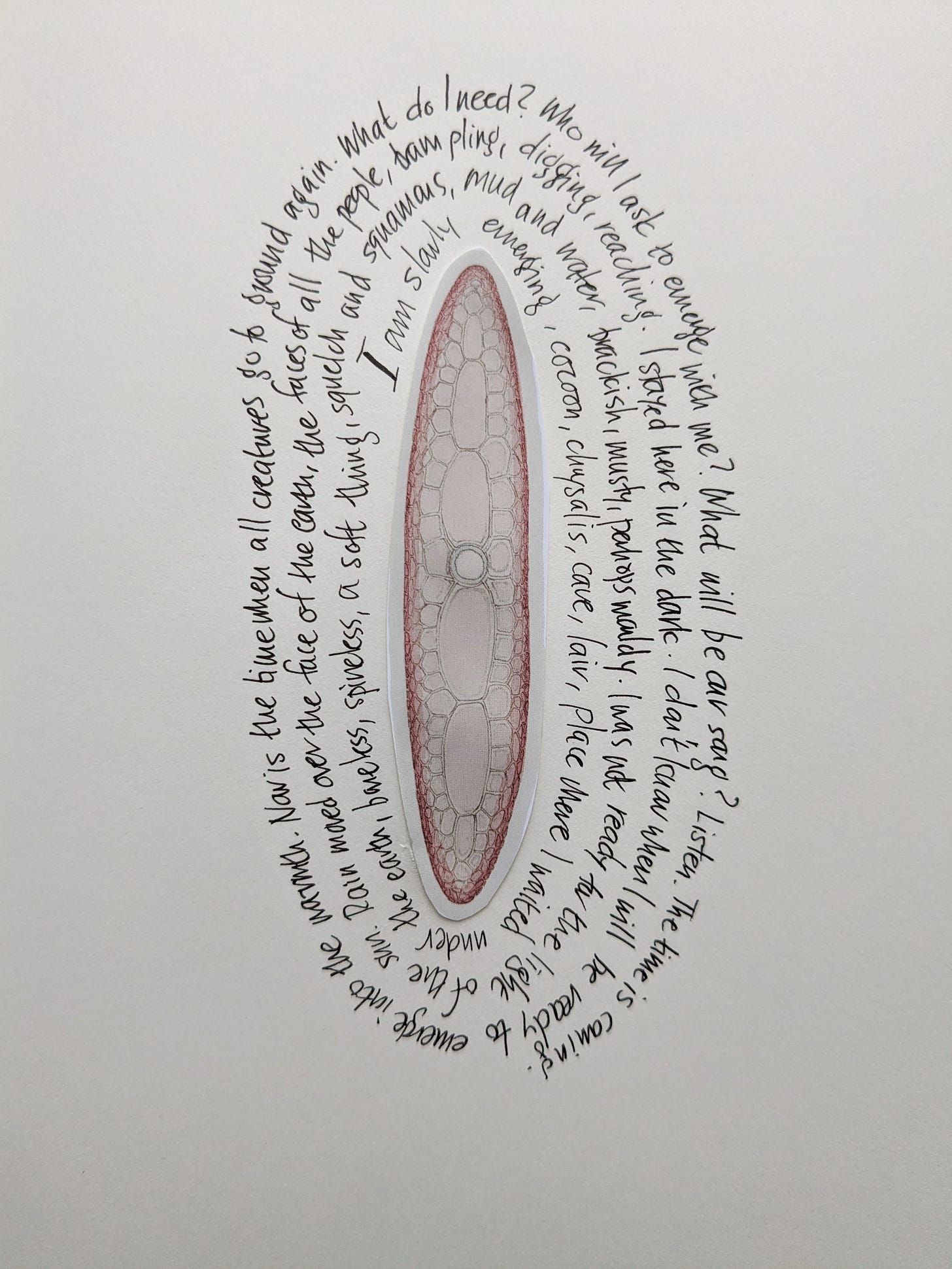

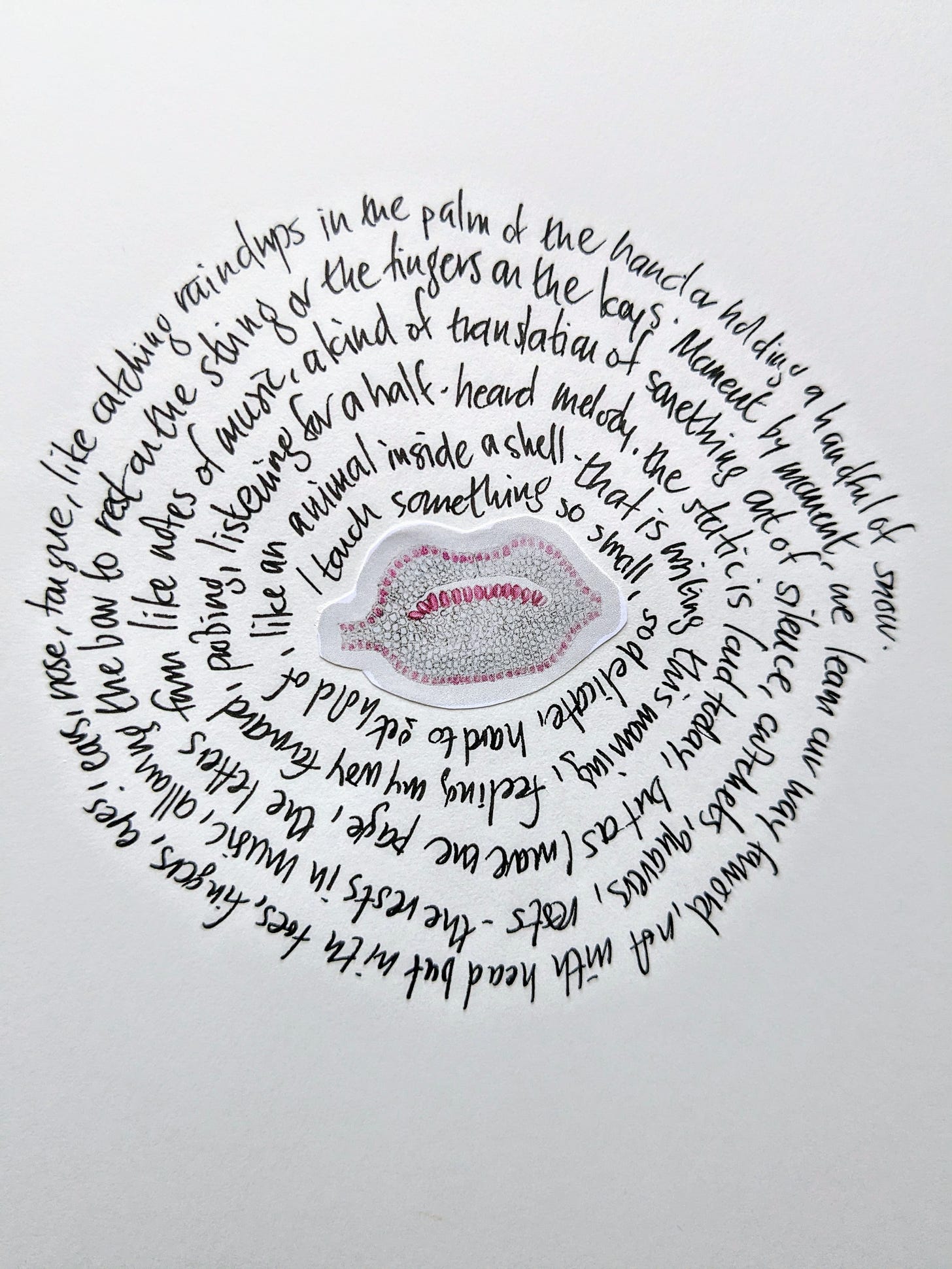

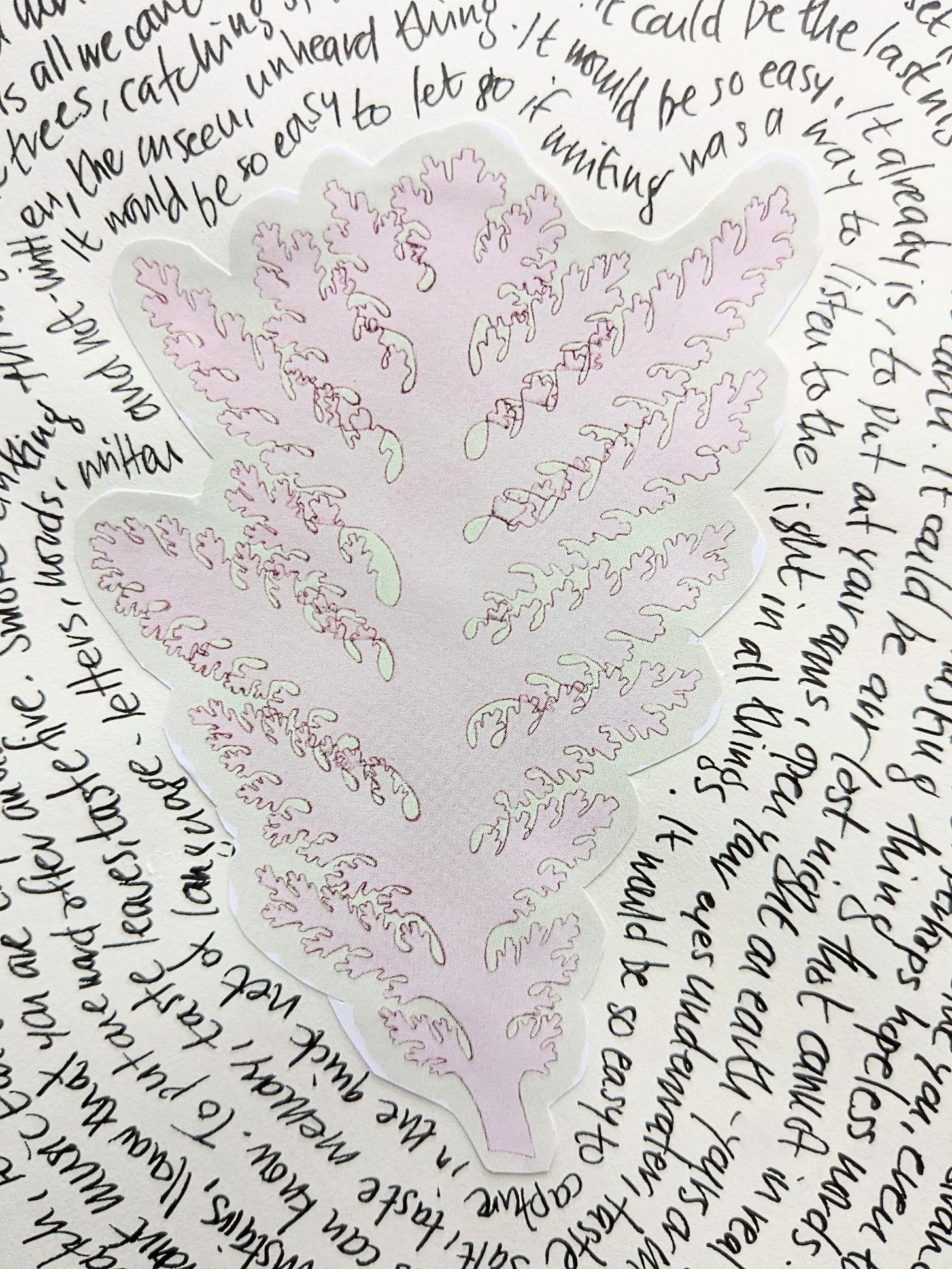

My recent experiment with my ‘thank you’ spiral writing practice has enabled me to notice, acknowledge and connect with all the many strands of my feelings following the sudden death of my beloved Dad.

For too long, because of my own experiences, I championed writing in a notebook with an unquestioned zeal — Let’s break away from our screens! Let’s grab our coloured pens! — until I began to work with writers who find writing in this way challenging or even impossible, for all sorts of reasons. Together, we began to explore how we can bring a mindful and self-compassionate quality of attention to allowing our hands to move over the keyboard; or how we can focus on feeling our body fully supported by a chair, the ground, our arm rests, or pay sensitive attention to the air moving over our skin as we speak into voice-to-type software.

What intrigues me about this process is that I don't need to feel calm and quiet in order to begin. There is something about the process of writing that helps me to slow down and let go into a more expansive, proprioceptive, fluid way of being.

Writing as paying attention

I’m not certain exactly when writer and Buddhist teacher

began her ‘small stones’ writing practice, but I know that it must have been well over a decade ago. ‘Small stones’ became so popular that, at some point, almost every writer I met was writing one each day.Satya explains: ‘A small stone is a short piece of writing that precisely captures a fully-engaged moment.’

‘Why write small stones?

When we translate something we’ve seen or experienced into words, it is necessary to pay more attention than we usually would. A few minutes of mindful attention (even once a day) helps us to engage with the world in all its beauty.’

I find it so interesting that Satya describes this practice not only in terms of paying attention and noticing but also in terms of the process of polishing the small stones or, as she says, ‘fiddling about’ until the words feel and sound right to you on the page. For Satya, although the process of finding the small stones is more important than the finished product, the process of selecting, crafting and polishing also seems to be a part of her practice of mindfulness.

Artist and writer Samantha Clark, who writes

here on Substack, draws on psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of ‘flow’ to understand the quality of ‘energised focus’ that is essential to her own creativity. Samantha writes:‘More and more I am coming to think that art is an antidote or counterpoint to the shallow and distracted quality of attention I can feel creeping up on me when I spend too long online.’

- Samantha Clark, ‘How to Draw Attention.’

Is mindfulness a ‘flow’ state? Perhaps. It’s interesting to ponder the similarities between mindfulness and flow. What do you think?

Befriending ourselves in the writing process

Jon Kabat-Zinn writes that ‘the core invitation of mindfulness is for you to befriend yourself.’

For me, this has meant cultivating the presence of a compassionate reader of myself and my writing on the page.

I’m constantly in the process of challenging that mean, nasty critic that lives inside me and turning instead towards a supportive inner reader, mentor or teacher. By strengthening my sense of this compassionate and accepting presence, a reader who receives my work with kindness, I’m not letting myself off the hook. It’s simply that, over time, I’ve found this gentle, playful writing companion far more motivating and helpful to my growth as a writer — and a person — than the bullies and monsters I used to hang out with.

One way we can get to know our inner friend or mentor is through compassionate letter-writing. A commonly used tool in Compassion Focused Therapy, it’s also a mindful and self-compassionate writing practice that any of us can adopt. A beautiful example of this, right here on Substack, is

where we are invited to write to ourselves ‘from a place of love and friendliness.’Psychiatrist and writer, Zebib K. A, shares a compassionate 'love letter' to a past self and you can find more wonderful examples under ‘Dear Past Me’ at the Herstory web site here too.

A slightly different approach is James Withey’s The Recovery Letters, a space where people can write letters to others, sharing their own experiences of recovery from depression, with the aim of bringing hope and comfort. Each letter begins: ‘Dear You…’

Writing as compassionate community

‘Self love cannot flourish in isolation.’

- bell hooks. All About Love: New Visions

In addition to cultivating self-compassion, the letter-writing examples above also create a powerful sense of community and compassion towards one another. Satya Robyn’s ‘small stones’ practice enables people to share their words and experiences. Writing, when we have the courage to offer and receive it in kind, supportive spaces, is particularly good, I think, at creating a sense of connectedness.

And perhaps as we learn to read, receive and offer compassionate feedback on the writing of others, we become more compassionate and supportive readers of our selves.

I don't have any easy answers to my original questions about writing and mindfulness. Mindfulness itself seems both elusively simple and highly complex. The mechanisms by which it is helpful to us are increasingly the focus of research. But I do believe that writing can help us to slow down, pay attention, experience more presence in the moment and connect with one another.

**One final important point. When we make time to let our overworked minds and bodies quieten, we sometimes find that thoughts and emotions that we’ve been suppressing come bubbling up to the surface. This can feel frightening or overwhelming and so it’s important to know that you’re not alone in this process. If this happens to you, please seek support from someone - a trusted person or a professional. Do also take a look at my post here which includes suggestions about keeping yourself safe when writing about difficult things.

What about you? Do you think of (some of) your writing as mindfulness? Is mindfulness practice part of your writing life? I’d love to know your thoughts.

And thank you! In this busy world, I really appreciate you taking the time to read my words.

Sophie x

This is a free Friday newsletter. Paid subscribers, keep a look out for Part 2 later in the week, where you’ll find some suggestions for practical mindful Writing Experiments.

+ A reminder about the invitation to paid subscribers to work with me on a piece of writing and share your story with us.

If you found this post helpful, I’d be so grateful if you could share it with someone who might find it helpful too. I love receiving your restacks and ❤️s, which help me to know what you most enjoy reading. Thank you!

Next dates for Writing Together

Thu 16 Nov at 7pm GMT

Sat 9 Dec at 5pm GMT

This live session is for paid subscribers, with a recording available for those who can’t join us live. Hope to see you there!

Throughout the month of November, I’m participating in #AcWriMoments, a 30-day global writing adventure.

Throughout November, I’m participating in #AcWriMoments These 30 gentle writing prompts have been created by writing scholars, coaches, consultants, and editors from around the world and curated byHelen SwordandMargy Thomas

I’m honoured to be contributing a prompt (coming up soon!) to this stellar group of contributors and I’m also joining in with the adventure. See you in the #AcWriMoments Comments?

What a beautiful article - lovely to find you here & thanks so much for mentioning small stones. That all feels like a very long time ago, but I still have a place in my heart for them!

Beautiful piece thanks 🙏🏼