Why don’t you just shut up?

Why we need to stop silencing ourselves and write the things we need to write.

My mouth is full of cake. Sponge mixed with the cloying sweetness of butter cream. I try to swallow but my throat closes up and my eyes fill with tears.

I hide my spluttering in my paper serviette. I can’t do this to Grandma.

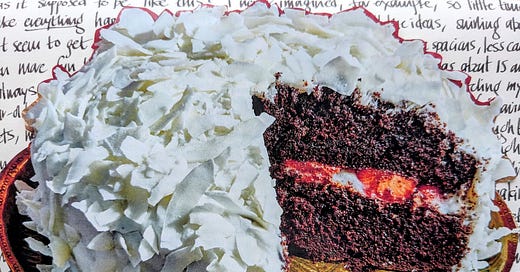

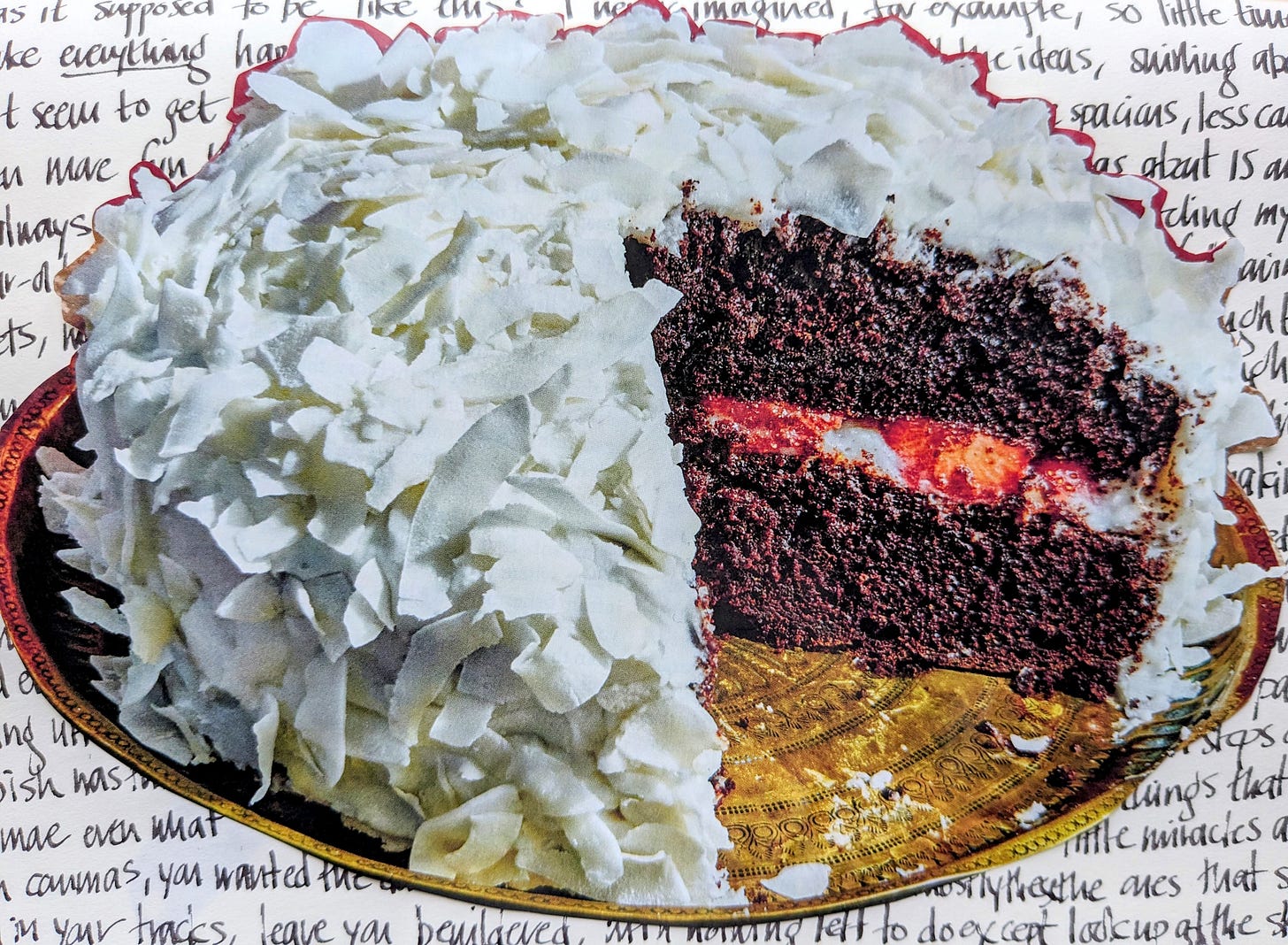

Grandma is the Grandma who bakes for birthdays. She has balanced this cake precariously on her knees in the passenger seat of Dad’s Nissan, all the way from her flat to our house. Now it sits in the centre of Mum’s best tablecloth, a six-layered triumph of alternating pink, vanilla and chocolate sponge, sandwiched with jam and buttercream. On top of the cake, more butter cream, whipped into peaks and sprinkled with hundreds and thousands. The colours from the hundreds and thousands are beginning to seep into the cream - pink, blue, yellow, brown.

Fortunately for me, everyone else around the table is watching my little sister, who has chosen this moment to have her own loud and alarming choking fit.

I make a grab for my glass, gulp warm apple juice and the wad of cake disintegrates, foaming and then swirling down my throat.

Relief. But my stomach still twists. The smell of the butter cream oozing on my plate makes saliva pool at the back of my mouth.

Across the table, my sister is laughing now, disaster averted. Grandma turns to me, smiling.

‘Delicious,’ I say, pressing the serviette to my lips. ‘Thank you, Grandma.’

‘Bless you,’ she says. ‘Another slice for the Birthday Girl?’

She’s already picking up the knife.

I don’t tell anyone how eating cake makes me feel. I’m already so used to holding the words on my tongue, so practised at swallowing them down that I don’t know how to begin to say them out loud.

As a child, so family legend goes, I had plenty to say for myself. I was the girl who was always chosen to do the church readings and take the main parts in the school plays. At ten, I read my prize-winning short story about trees on BBC Radio 4.

It’s not as if I didn’t have a voice.

I was told repeatedly that I was well-spoken. In the class-obsessed Britain of the 1980s, this meant saying the right thing in the right way at the right time. The kids at school called me posh. My Mum, a drama teacher born in Lancashire, had been sent for elocution lessons. My parents were in agreement that I shouldn't inherit my Dad’s flat West Yorkshire vowels. And so I moved between two voices: the home voice I used for speaking ‘nicely,’ and the school voice I used to try to fit in with everyone else.

Somewhere along the way, I lost all sense of what my own voice sounded like. I was too busy stretching my mouth into the right shape, dropping or enunciating consonants as the situation demanded.

As I got older, my voice got smaller and smaller. I would flounder, run out of air. I developed asthma and my inhaler made my voice thin and strange. Saying anything in class became an agonising ordeal of controlling my breathing.

I am fifteen when I am summoned to the headteacher’s office.

I notice that my hand is trembling as I knock on his door. I squeeze it into a fist and push it into my pocket.

The Head gestures to the two chairs in the corner of the room. In one of these chairs, Nathan Goodall (not his real name) is already waiting. That’s when I realise what this is about. The familiar ribbon of nausea unfurls from the bottom of my stomach.

I sit down. I smile.

The Head is saying something. ‘... Voted and discussed… staff and students… unanimous decision...’

Nathan is nodding, trying not to look smug. They are both looking at me now, expecting a response.

I smile again. ‘Thank you, sir.’ That is how I accept the position of Head Girl, a job that no one wants, least of all me.

As we climb the stairs back to the chemistry lab, Nathan is grinning. Nathan is the new Head Boy.

‘Bad luck for us,’ he says. ‘But at least my Mum’s gonna be made up. She might give me the money to buy 750cc Grand Prix this weekend.’

I dig my nails into my palms.

Over the past year, I have managed to achieve my main goal in life, which is to fade quietly into the background. The mean girls have stopped singling me out for attention. My shoes are the right kind of shoes. My hair is, finally, the right kind of hair (well, as much as anyone’s hair can be in the late ‘80s). I don’t want to stand out.

I especially don’t want to spend the next year sitting on the stage during assemblies. Just imagining this makes my face go hot and my skin itch.

I really don’t want to be Head Girl.

But I don’t say anything.

"Don’t smile so much, sit up straight, bathe every day, and above all Don’t Say It, all those sentences that come ready-to-say on the tickertape at the back of my tongue."

- Susan Sontag, Reborn: Early Diaries 1947-1963

It’s 2006 and I’m angled on the edge of the sofa in my living room, staring into the lens of a video camera. I’ve recently set myself up in business as a therapist and writing teacher. I have an idea that I can film myself talking about my workshops, a bit of DIY marketing that might help me find participants.

Everyone does this now, of course, just by pulling their phones out of their pockets. But back in 2006, it feels new and bold and risky. Who do I think I am? Will I look like an idiot?

I redo the video a few times, trying to get it right. Then I post it on YouTube. When I check back a few hours later, I find this comment: You look like a man and you sound like a strangled cat. Why don’t you just shut up?

My face burns. My stomach twists. I want to take the video down. I want to curl up on my bathroom floor and cry.

My partner, an IT specialist, springs into action. It takes him only moments to identify that the author of the comment is a known internet troll. This is the first time I’ve heard the word ‘troll’. It’s the first time I realise that there are people who spend significant amounts of their time making comments about women on discussion boards and in chat rooms and that there is a special noun for them.

I report the comment to YouTube. I write a firm but polite note saying that I find this comment insulting and unacceptable. When there’s no reply, I write another note pleading with them to remove the comment. Three weeks later, I receive an email stating that they have investigated my complaint and cannot uphold it, that it does not contravene their Terms Of Use.

Why don’t you just shut up?

And so I do what I have always done. I turn to the page to try to say what I want to say. Perhaps it will be easier, I think, in the quiet and space of the familiar white page, for my whirring brain to summon the words, to put them together in some kind of order.

My first novel, The Dress, is a bestseller but the UK cover is all wrong. (The cover of the second novel is even more misguided.) I try to explain to the marketing team that I don’t think the covers are helpful; that the books grapple with challenging subjects such as sexual assault and racism and identity, as well as magic and the relationships between women. I learn that none of this matters, that this is the kind of branding that is used for ‘commercial women’s fiction.’

Joanna Russ published How to Suppress Women’s Writing in 1983. In this book, her exasperation at the false categorisation of ’women’s writing’ is palpable. She examines the ways in which women have been deprived of a female tradition, their writing dismissed because it is seen as writing about women’s lives and subjects. Autobiographical experience is called ‘confessional’ when written by a woman but not likely to acquire that label if written by a man. Russ summarises the ways in which women over the last two hundred years have grappled with a central dilemma, which is this: Good girls are deemed not to know enough about life to write interesting and compelling material. But if girls do write things that compel their readers, they can’t be good girls. They must know too much. In fact, they should be ashamed of themselves.

Thirty-five years later, in her 2018 foreword to Russ’s book, the feminist critic and author Jessa Crispin, writes: ‘I am worried that readers of this book will mostly see themselves as the suppressed and not the suppressors.’ She points out that we all have our subconscious biases and that we are rapidly ‘subdividing into tiny, highly specific demographics’ shaped by social media bubbles and algorithms.

In Crispin’s case, this might mean that she is ‘only going to be encouraged to read the works of other white, middle class, heterosexual, spinster, Cancer-sun and Taurus-rising women who come from the rural mid-West but now live in an urban area.’ She suggests that the idea that literature fosters empathy is a ‘cliché’ and that we all need to ‘aggressively work against the impulse to treat literature like a mirror.’

I believe this to be true. And it’s not just true of women.

I’d like to hear your voice and read your story. But perhaps, before all of this, you might just need to hear your own voice, for yourself, loud and clear, inside your own head.

I don’t think any of us should shut up anymore.

My daughter is chosen for the role of Angel Gabriel in the school Nativity play. She is four years old. She hasn’t yet learned that she's supposed to be afraid of speaking up, of speaking out loud.

She memorises her lines with little effort, reeling them off in the back of the car: Listen to me. I am an Angel of the Lord. I bring you good news of great joy.

On the night of the performance, I help her to fasten the gold nylon dress, attach her halo, her glittery wings.

When she steps to the front of the stage and raises her arms, I’m recording it all on my phone for her dad, whom I left earlier that afternoon in the ICU, in the care of a specialised team.

I bring you good news of great joy, she says and her voice is clear, strong, unwavering in the darkened theatre.

It seems to me that my daughter knows exactly what she wants to say. She stands with her feet apart, looking straight out at the audience. Her confidence, amid the chaos and complexity of our family’s life over the previous months, moves me to tears.

At the end of the performance, as we make our way to the stage to collect our angels and shepherds and sheep and wise men, one of the mums shoots me a wry expression.

‘Well, who’s got a very big voice?’ she says.

I don’t think it’s intended as a compliment.

Have you ever been told that your voice is too big, too small, too much, not enough? Do you find yourself second-guessing, editing yourself, hesitating to tell your story, perhaps even to yourself? Do you tend to tell yourself that writing in your journal is a bit self-indulgent?

These are just some of the many ways that we keep ourselves from ourselves and our creativity.

Restorative Writing Season 1: Core Practices offers a supportive space for you to develop your creative confidence and write what you want or need to write.

Paid members receive:

⚡️The Restorative Writing toolkit and resources, designed to help you to get the most out of the materials and your writing.

✎ A syllabus of seven ‘classes,’ each consisting of a short video and a structured writing ‘experiment’ or prompt.

🌼 Three Writing Together live sessions on Zoom (with partial recordings) + a special Midsummer Writing Together Zoom celebration on 22 June.

✨ Community space where you can share your experiences, questions and reflections (and some of your writing, if you so choose, but there is absolutely no expectation of this).

You can expect to:

Find out more about the practice of restorative writing and establish a creative writing practice that restores your energy.

Reconnect with your creativity and your belief in your writing and your self.

Learn creative ways to rest deeply.

Gain new knowledge about what really works for you and your writing and how to contine to nurture your practice in the weeks and months to come.

Become a more self-compassionate and constructive reader of yourself on the page. This can often lead to new insights and understandings about your life and experience, as well as your creative process.

Find supportive community. You don’t have to do this alone. On the other hand, there’s absolutely no pressure to join in with the ‘group’ parts or share any of your writing.

Subscribe now and you can join us for our next Writing Together live Zoom session on Wed 10 April (partial recording available) and get access to all my paid posts plus my mini-course, Creative Rest.

Paid members, please find this week’s Writing Experiments beneath the pay wall.